Insect Machines

A new paper discusses differences between Bitcoin mining & AI data centers and uses modeling to substantiate miners' claims that their operational flexibility contributes to reduced carbon emissions

On a recent flight I killed some time by reading a new paper by Troy Cross and Margot Paez of the Bitcoin Policy Institute. “The Locust and the Dung Beetle” describes the differences in emissions output from Bitcoin mining facilities vs. AI computing. Below are the main takeaways (the insect comparisons are already familiar to many of you).

DUNG BEETLES: Bitcoin mining is comparable to an energy-intensive lottery; miners are location-agnostic and price-sensitive consumers of electricity whose key traits are flexibility, scalability, and portability. Miners, in the style of dung beetles, are relentless seekers of waste energy who can mitigate the effects of natural gas flaring in remote oil fields or co-locate with solar or wind installations for a plethora of benefits.

LOCUSTS: In contrast, the paper compares AI computing to locusts, which feed on valuable crops. AI data centers’ power usage is typically inflexible, location-dependent, scale-dependent, and price-insensitive.

CAVEATS: AI computing may eventually become more like Bitcoin mining as compute loads shift to the cheapest power source. And there are times when Bitcoin mining exhibits locust-like traits, e.g., when mining is profitable on all-available electricity.

EMISSIONS FROM MINING vs. EMISSIONS FROM DATA CENTERS: Using marginal carbon dioxide emission factors, the authors computed the amount of emissions that are avoided when miners reduce their power demand in reaction to peak demand or high electricity prices. The authors then compared this data to a firm-load data-center model that never reduced its power in response to demand or price signals. The findings are interesting.

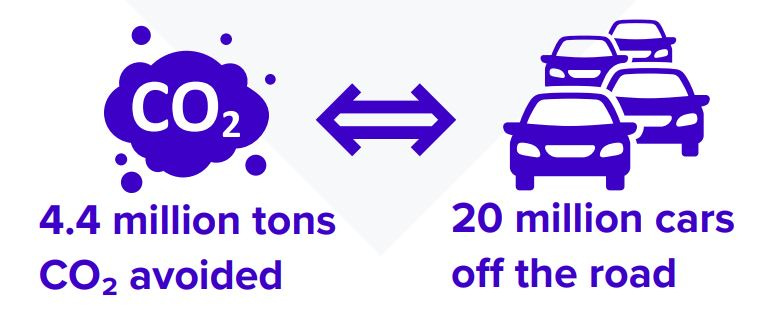

REDUCED CARBON EMISSIONS

The authors gathered power usage data from 10 bitcoin mining companies in the United States/Canada and found that these companies curtailed power usage between 5% and 31% of the time. Over a period of three months, the miners reduced their carbon dioxide emissions by 13.6 kilotons. If this data is representative of the entire network, the authors argue, “the marginal impact of miner flexibility is equivalent to avoiding 4.4 million tons of carbon dioxide annually, or taking 20 million cars off the road.”

That’s a bold claim and sits in marked contrast to environmentalists’ oft-repeated criticisms of Bitcoin mining. The findings also add more arrows to the quiver of claimed Bitcoin benefits within the energy sector, many of which are stockpiled here.

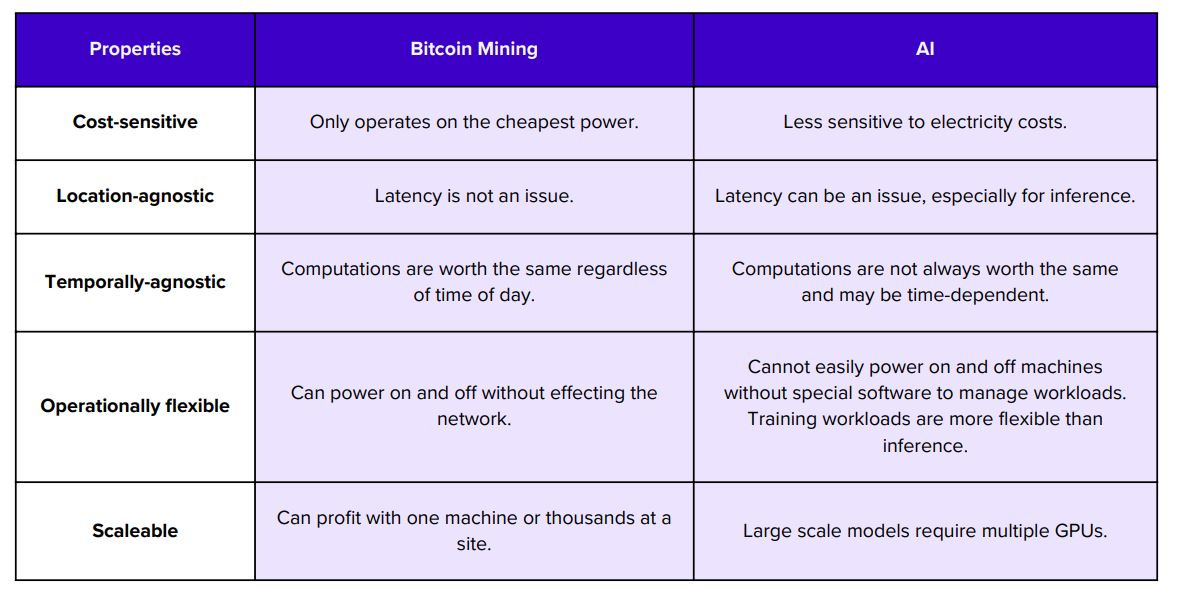

HOW BITCOIN MINING DIFFERS FROM AI DATA CENTERS

The paper goes to great lengths to differentiate Bitcoin mining from AI data centers, as the two are often conflated, specifically by regulators. The authors note that data centers have a near-constant uptime versus the more variable uptime of Bitcoin miners.

“Traditional data centers, and particularly the new AI data centers, are locusts,” the authors reiterate. “Just as locusts descend onto a farmer’s crop, eating everything in sight, traditional data centers consume power on their own terms. Their contracts require 99.99% uptime, so they cannot turn off their machines when grids are under stress, such as during a heat wave. Their profit margins support paying high prices for power, so they outcompete local buyers. They require special water-intensive cooling and low-latency internet connections to major metropolitan areas. This means the data centers are coming like swarming locusts, and they will consume as much energy as those grids can produce, raising prices and increasing emissions.”

Bitcoin mining, on the other hand…

…is a dung beetle, which uses animal waste both as a food source and as a breeding chamber. We call mining a dung beetle because the design parameters of bitcoin make mining unprofitable on all but the cheapest energy in the world. (Few miners can operate profitably above $0.05/kWh, and most are paying far less.) Miners can also move to any location in the world without impacting their profits, and they can turn their machines on or off in mere seconds. That cluster of features means miners are engaged in a relentless world-wide search for waste energy…When a bitcoin mining data center is connected to a grid, its machines will simply turn off whenever power is scarce and expensive, and turn back on when power is abundant and cheap. So, while bitcoin mining consumes large amounts of power, just like the lowly dung beetle, it uses primarily what others leave behind.

The paper provides the following, at-a-glance comparative chart for Bitcoin mining and AI data centers.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Below are the paper’s policy recommendations.

Set price structures that incentivize flexibility. “We caution local policymakers and grid operators that have control over rate structures to not assume that data centers, and in particular, Bitcoin mining, are firm loads,” the paper states. I see this as a subtle exhortation for regulators to be hyper-cognizant of each entity’s capacity to participate in demand-response programs, price arbitrage, or Time-of-Use tariffs and to incentivize flexible load whenever possible. (It’s worth noting IMHO, that this will require a level of sophistication that most lawmakers and decisionmakers lack.)1

Reform transmission rules and reduce interconnection queue wait times. The authors note that the majority of active capacity in interconnection waiting queues have online dates between 2025 and 2028, which aligns well with the timeline for rapidly accelerating data-center construction. “The biggest challenge,” the paper says, “is making sure that these generation projects are seen through to completion.”

Encourage the integration of computation and generation. The authors project that data centers will continue to grow in size, such that 1GW centers will eventually be commonplace. To be able to supply enough power to these sites, new power generation will need to be commissioned. Regarding loads that can provide high flexibility, the authors highlight that we will soon see increasing numbers of renewable energy companies dedicate a percentage of their power to these compute centers to boost baseline revenue. “Policymakers,” the paper says, “should encourage these activities because they will ultimately accelerate the build out of clean energy.”

Exercise caution with energy estimates. The authors warn that estimating energy use is difficult, and forecasting years ahead is fraught with great risk. “Extreme predictions of growth have a track record of being mistaken,” they write, “and lawmakers should treat them as highly provisional.”

Therein lies my attempt to condense the 21-page paper into a few blocks of text. I’ll try to do this more frequently with white papers and longform analyses that surface.

LOOPHOLES, CLAWBACKS & ADDITIONALITY

James Sallee at UC-Berkeley has identified a loophole in the Inflation Reduction Act that, humorously, may incentivize natural gas, which of course should be the bane of all good-thinking people on the right side of history, who now refer to it as “fossil gas.”

At issue is neutrality. One function of the IRA is that it sunsets existing and “cornerstone” renewable policies and transforms them into a technology-neutral iteration. In theory, this ensures that subsidies are available for any viable source of clean energy. New language therefore allows any power generator whose “anticipated greenhouse gas emissions rate…is not more than zero” to be subsidy-eligible.

While this change might facilitate new or cutting-edge ways of generating clean electricity, it may also provide opportunities for combustion or gasification technologies, e.g., carbon-negative scoring gas plants that burn biogas.

Sallee explains why IRA proponents should worry:

Could biogas emit “not more than zero” carbon? Yes. If methane would otherwise be released into the atmosphere, then capturing and burning it is arguably “negative emissions.” This is certainly how California views the matter. It credits dairy biogas with negative emissions under the low-carbon fuel standard. It is not hard to imagine Treasury writing a check to gas generation facilities if they have receipts to show that they are sourcing gas from the neighborhood dairy or local landfill.

Biogas is the same chemical object as conventional gas, so there is no way to construct a “biogas-fired” plant. You just build a natural gas plant and then source a clean input, which means you could always switch back to dirty fuel later.

In this context, a gas plant could convince the Treasury that its operations are technically “clean” — thus obtaining a subsidy — and proceed to burn conventional gas for decades. While an existing IRA clawback provision may prevent such scenarios, Sallee is skeptical of whether the clawback is a formidable enough disincentive.

Measurement challenges also muddy the waters. “Measuring the lifecycle emissions of biogas and biofuels has been particularly vexing,” Sallee notes. “But the problem is even harder than that, because even if a gas plant is literally burning the gas from a landfill or a farm, this does not mean it is reducing emissions if the landfill or farm would have captured and used that gas for some other purpose.”

This constitutes additionality, which is baked-in to subsidy-based approaches, whose eligibility rules are premised on a counterfactual: had this policy not existed, what would have happened? But such a scenario can never be observed in empirical fashion.

And pertinent to the locust theme above, Sallee expresses concern that new levels of load growth via AI data centers (and electric vehicles and heat pumps) may prompt developers of gas infrastructure to seek ways to pass 50% of their construction costs on to taxpayers.

We shall see, I guess, as the IRA continues to contort itself into reality.

CALIFORNIA & DEGROWTH

Over at Construction Physics, Brian Potter diagrams the process by which California became an anti-growth state whose policies radiate throughout the rest of the nation. He outlines the genesis of the state’s optimistic, formerly pro-growth attitude, noting that by 1910 California was producing 73 million barrels of oil per year, which was more than any country outside the U.S. and constituted more than 20% of world production. California led the nation in oil production until 1927, at which point Texas became king.

But several factors kicked in that precipitated an entirely different state of affairs. By the 1960s, new housing became harder to build, and investment in the requisite infrastructure collapsed. Home prices surged.

How did this happen? He writes:

Decades of growth began to strain the environment that had attracted people to California in the first place. Residents found themselves surrounded by polluted water, poisoned air, and a destroyed landscape. Views and natural beauty were increasingly spoiled by overhead power lines, outdoor advertising, freeway overpasses, and thousands of identical houses. Infrastructure like roads, schools and sewer systems were stretched to their breaking point. Crime was rising, and neighborhoods of single-family homes with largely white residents were being encroached on by apartment buildings housing the poor and minorities.

In response to this unwanted change, Californians began to create land-use restrictions that would curb growth, help stop environmental harm, and limit the influx of new residents. When this drove up property values, Californians then passed Proposition 13, which cut property taxes, reduced the government’s ability to fund services, and locked in the low-growth culture that had taken root.

A few other takeaways:

Some origins of the anti-nuclear movement in the U.S. can be traced back to protests of the Bodega Bay nuclear power plant in California.

In 1970, the California Environmental Quality Act was passed, which was a much more muscular/statewide version of the federal NEPA act. “By 1976,” Potter writes, “4,000 CEQA-mandated environmental impact reports were being produced each year, four times the number of impact reports produced by the federal government.”

Anti-sprawl measures initiated by the California Coastal Commission required builders of power plants to demonstrate that “energy conservation efforts, including concerted efforts by the applicant within its service area, cannot reasonably…eliminate the need for the proposed facility.”

Potter concludes that any return to a pro-growth mindset will require that Californians embrace the virtues of growth, whose optimism presupposes that any associated problems can be overcome.

MORE SCATTERED THOUGHTS ON DEGROWTH

An anti-growth mindset necessarily requires the elimination of fossil fuels, which, as mathematician and environmental policy expert Michael Goff notes here, may not even be feasible until the year 2420 (i.e., 396 years from now).

“Hopes for a faster transition,” he writes, “rest heavily on learning curves, the idea that as more wind and solar energy are deployed, the cost of these technologies will fall, thus stimulating further deployment…but for now, if one really believes that climate changes poses an existential threat to civilization, then pinning hope for a solution on learning curves is an extraordinarily reckless move.”

And, as alluded to previously, the environmental movement has a well-established animus toward nuclear power, which helps stall the development of that particular resource (and by extension, growth and prosperity). Such animus, and its attendant propaganda, lends itself to regulatory barriers that impale nuclear energy by making it unaffordable. Per Jack Devanney:

The reason why nuclear power is so expensive is a regulatory regime which by design is mandated to increase costs to the point where nuclear power is at least as expensive as coal. In such a system, any technological improvement which should lower cost simply provides regulators with more room to drive costs up. This same regime does an excellent job of stifling competition and technological progress by erecting multiple layers of barriers to entry.

This trajectory may be changing though, as some have described the Biden administration, such that it still exists, as the most pro-nuclear executive office of all-time. (A silver lining, I suppose, to the rancid falseness, authoritarian mandates, anarcho-tyranny, censorship, election fortification, dementia, incontinence, divisiveness, gaslighting, fear-mongering, corruption, inflation, malfeasance, weaponized immigration, lawfare, psyops, gay race communism, and blithering idiocy for which it is otherwise known.)

ENERGY LINKS

How About Electrification-Specific Marginal Cost Pricing of Electricity? “…marginal cost pricing promotes economic efficiency. But it can also trigger a redistribution of bills across customers if applied retrospectively on all customer usage. It is is politically untenable. Is there a better way? Yes, only apply marginal cost pricing at the margin for consumption associated with the installation of heat pumps, EV chargers and other electrification technologies.”

Quantifying California’s Brave EV Future: “…will there be enough electricity? As it is, we may expect [Battery Electric Vehicles] to log around 13 billion miles on California roads this year. At 3.5 kilowatt-hours per mile, that will only burn through 3,700 gigawatt-hours, which is only about 1.3 percent of the not quite 300,000 gigawatt-hours we’re likely to use this year. But if 50 percent of cars on California roads were BEVs, we’d need 48,000 additional gigawatt-hours, plus a ten-fold increase in the high-voltage distribution lines needed to deliver fast charging to millions of impatient motorists.”

The Impact of Regulatory Reform on California Solar: “Renewables, being positioned behind the distribution and transmission system, have disrupted the traditional pricing model. As a result, additional services required for reliability—such as Peak Capacity, Dispatched Ramping, Synchronous Power, System Strength, and Voltage/Frequency Stability—have now been unbundled and are charged at a fixed rate. Previously, consumers could avoid these costs, effectively passing the expense of maintaining a stable supply onto utilities. This led to financial difficulties for Californian utilities, and with politicians heavily invested in the green narrative, solutions for corrective action were limited. However, last year, the regulator unintentionally arrived at a promising solution, when out of desperation changed the net metering rules, because wealthy users were not paying their ‘fair share’ for maintaining the grid infrastructure.”

What Would Consumer-Related Electricity Look Like: “One solution to the monopoly problem is to allow new, private utilities to develop and compete wherever they make sense…Sometimes the state level is the place to look for new answers. And when it comes to the idea of enacting truly competitive reforms in the electricity sector, states are in control. All it would take is a modification of the statute that created the state’s public utility regulations in the first place and a clear declaration that new private utilities—if they are not connected to existing infrastructure—will not be subject to monopoly regulation.”

MISCELLANY

And Suddenly Things Change: “Everything that can break is breaking: stock markets, bond markets, the galaxy of derivatives — bets on this and that, which will never be honored. Banks are next. Gold and silver are hanging in there for dear life just now, because they’re actually worth something.”

Frontier Cities: “Like many other moments in American history, we find ourselves at the advent of a technological innovation era that has the potential to significantly increase human freedom. We must grasp it. America must, as it has for centuries, set out toward that goal. We don’t need to colonize Mars, we don’t need new think tanks, and we don’t need to retreat into siloed wellness communities. We can only achieve a new era of American expansion through acquisition of land, city building, and frontier technologies. Significant support from government leadership will be necessary for this to succeed.”

Mimicry and Mastery: “…one of the great traps of modern society—…society at a global scale—is that a mediocre life, a life of unfreedom, can be rendered not just as habitual but as desirable. This is noticed by Ernst Jünger in his wonderful 1951 book The Forest Passage…‘the real issue,” Jünger observes, ‘is that the great majority of people do not want freedom, [and they] are actually afraid of it.’ But how is this possible? How can people end up, often so easily, wanting what is not good for them?”

Start a Cult: “Create a vision of a world on fire, an all-consuming idea of what could be. A bright paradise that will be a shining light. Keep it esoteric to stay niche, to make them curious.”

You Can Probably Just Have It: “The right attitude and body language can get you almost anything you want—at almost any time, in almost any place. If you are nice, confident, and happy—with your chin up and shoulders back—and you act like the thing you want is obviously the thing that is going to happen, you would be amazed at what you can obtain.”

Of note, a 2021 CoinDesk article, which described Senator Ted Cruz’s comparison a few years back of Bitcoin mining to fracking: “His comments were apt: Bitcoin mining appears to be wholly consistent with the goals of environmentalists in the U.S., as it safeguards grids made unstable by new wind and solar assets; monetizes hydro and nuclear when the grid is not a buyer; and settles into off-grid niches like waste natural gas. That he has achieved this level of sophistication on the topic is truly remarkable, as bitcoin is not a policy priority of his. One can only hope that the rest of his Senate colleagues do the same.”